Around the world, societies are looking for ways to live with climate change. Adapting to a hotter and harsher future means scientists, governments and communities must find ways to protect essential resources like land, homes, farms and water. Buildings need to stay cooler and withstand storms and floods, and crops need to survive more severe rains and droughts. Biologist and climate change scientist Serafino Afonso Rui Mucova studies how nature responds to human activity and changing weather in Mozambique, and how people can help ecosystems cope with climate change. He spoke with The Conversation Africa about what’s holding Mozambique back from adapting to climate change. This article is written by Serafino Afonso Rui Mucova, Lúrio University.

What are some of the biggest climate problems in Mozambique today?

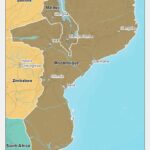

Mozambique represents just 0.4% of the world’s population. It contributes less than 0.1% of global greenhouse gas emissions. But it has been identified by climate scientists as one of Africa’s climate risk hotspots.

The country faces droughts, floods, biodiversity loss, rising sea levels, and recurring extreme tropical cyclones that affect development and livelihoods.

How is Mozambique adapting to life on a hotter planet?

Mozambique is lagging behind in adapting to global warming in three ways. First, it has a deficit or shortage of scientific data. In Mozambique, climate data stations are scarce and inadequate. The available datasets (meteorological and climate information that researchers rely on) are fragmented. This means that climate data is incomplete, scattered and inconsistent.

Long-term records haven’t been properly kept and are unreliable for decision-making. This scenario weakens Mozambique’s capacity to prepare evidence-based adaptation plans and to anticipate what climate disasters are coming.

Second, there is a capacity deficit. Governments, ministries and local administrations rely on only a few specialists to design, plan and execute climate change-related projects. These include coastal protection works, irrigation projects, dams, and water supply and sanitation systems that can survive extreme weather. Other examples are early warning systems for cyclones and floods, resilient road construction, reforestation, and mangrove restoration.

These project portfolios require well-trained teams of environmental and social specialists, civil engineers, economists and architects who have the same goals. But experienced and qualified professionals tend to migrate to donor-funded projects or international consultancy projects, where prospects for personal development, salary, working conditions and careers are better.

As a result, government and local administration sectors lose technical capacity. This weakens and limits the ability of institutions to design, plan, supervise and sustain climate change adaptation efforts, resulting in delays or incomplete projects.

Third, there is a financing deficit. This is a critical gap. Many climate adaptation projects don’t move beyond being ideas. The countries in Africa most at risk receive only about 11% of the climate adaptation funding they need. The gap between what is requested, what is needed, and what is disbursed remains huge.

Finally, global leaders and negotiators must recognise Africa not as a systemic recipient of international aid, but as a co-developer of the planet’s climate future.

What needs to happen at COP30 to solve these problems?

COP30 needs to move beyond promises and commitments to actions that can be tracked and measured. Adaptation must be seen as a global public good. When African health, education, food, water, coastal, roads and energy systems are working well, the whole world benefits. This is because conflicts, stability, migration, trade and security are all affected by climate change. Their effects extend beyond the physical borders of countries.

From my work in Mozambique, these are the three most important things that COP30 needs to do:

First, invest in science and climate data systems for the whole continent. Weather and climate observation stations and monitoring networks, research centres, and universities must be substantially strengthened and funded. They need to be able to produce projections, modelling and locally relevant climate risk maps.

These maps combine data on climate hazards such as coastal erosion, floods, sea level rise and prolonged droughts with data on population settlement, resources and infrastructure.

They then generate a picture of areas most at risk which can be assisted first. Without African climate data, there will be no African solutions.

Second, dedicated financial packages and adaptation funding channels must be set up. These channel funding from global funders and development banks to projects on the ground. Local authorities – for example, municipalities or water and sanitation utilities – need flexible and predictable access to funds instead of sporadic donor-funded projects.

Third, ways for Mozambican climate adaptation projects to access global funds must be reformed. Current procedures restrict access and are too complex. They involve excessively lengthy application forms, technical and financial feasibility studies, and multiple rounds of technical and financial evaluation.

Each stage costs governments money. It also demands time, consultants, and specialised knowledge that government sectors do not possess. As a consequence, promising projects remain on paper.

Africa’s main challenge isn’t just coping with climate change but rethinking how it grows and develops so that its cities, farms and infrastructure can all cope in future with the reality of a changing climate.

If COP30 succeeds in transforming rhetoric into concrete mechanisms or actions, it will mark a historic turning point and fulfil its mission. If COP30 fails, the credibility and role of the entire annual global climate change conference process will continue to deteriorate.

Serafino Afonso Rui Mucova, Senior Lecturer and Researcher, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Lúrio University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.